Lab Diaries 4: Attention: Chevreuil!

Published:

Out of one cratered beady eye drools morsels of rotted flesh. It’s neck punctuated with fungal tumors with hovering mosquitoes awaiting a death long overdue. Nostrils flaring spasmically as the demons roam the halls of its skull. My jerky defence and screams of warning fall upon unattending ears. The single functional eye steely stares through my physical being. Bambi ain’t an innocent baby no more.

But there are other cute Bambis around Anticosti Island! In 1895, a Belgian chocolatier by the name of Henri Menier decided that this Jamaica-sized island was going to be his personal hunting paradise. Back in the day you could buy a provincially-sized island for a quick $125,000, fill it with 220 deer, 20+ bison, a few moose and caribou and proceed to visit it a total of 6 times without the international community calling foul. Imagine the effort to bring 220 live deer onto a boat WOW. A brazen display of wealth immortalised by a landscape-altering infestation of deer. Horizons of tall grasses dotted with pairs of kangaroo like ears. No natural predators! One of those bizarre places where both deer and hunters win.

It’s over here where the great Algae-WISE (WaterSat Imaging Spectrometer Experiment) project has been underway. Led by Simon Bélanger and Fanny Noisette, this massive team of more than 50 scientists specializing across all atmospheric levels from the weightlessness of space down to the weightlessness of the ocean are currently underway trying to put a finger on how we can detect algae use new technologies like hyperspectral imagers (imagine seeing EVERY wavelength) in satellites, airplanes and mounted on SCUBA divers. I managed to weasel into the terrestrial team because of my chops as a scientific diver as well as my interest in using this fancy new multispectral camera I got strapped onto a drone.

A quick crash-course into optics! Ever wondered why chlorophyll is green in color? If you look at the spectrum of colors, chlorophyll loves to absorb blue and red - using these wavelengths to power photosynthesis. However, it isn’t interested in green and reflects it back allowing us to see a leaf as a green object. This works the same for the indigo dye which at one point was all the rage in the Spanish empire (shakes head). The Indigo pigment doesn’t care too much for light in the wavelength of 400 nm - 500 nm (nanometers) which are the the wavelengths of blue. As it reflects it back, we see blue and a Spanish galleon arrives at your local beach. Now chlorophyll also reflects other wavelengths that we may not be able to see - like infrared waves! Using special sensors that pick up infrared waves in a similar way to how cameras take photos, scientists identify these infrared waves and visual waves and put them into a NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) formula to identify where chlorophyll exists and not! Super rad. This, in the marine environment is a challenge because of water! Water is a greedy molecular monster that rapidly laps up low energy wavelengths like those of infrared waves, so it’s a bit more of a challenge to detect chlorophyll in ocean based vegetation like kelp. We get to work around this by looking for the Red edge waves (~717nm) which is juuuuust in between the red we see and the infra-red used to detect NDVI. These waves have more energy and have more of a chance of being reflected back, so using a camera like the Micasense RedEdge-M, I might be able to detect where these algae are in the sea!

After driving almost 900 km to get to CGQ’s center in Chicoutimi I finally got access to this imager. Now, I had to find a way to mount it onto one of our more heavy duty drones - the DJI Inspire 1: an old bull with dusty batteries (one of which died on me the day before I left for Anticosti) that was the only drone in our fleet that would handle a payload like this imager. I enlisted the help of the internet’s thingiverse for some 3D-printing files and my prof’s tech genius son, Noah Johnson to show me how to 3D print some objects and lo and behold, I made a beautiful low weight cradle that would snap onto my drone and hold the imager. Granted, there was a frighteningly large amount of zipties, rubber bands and velcro for my liking but hey, this jugaad is as solid as it comes. Unfortunately, I couldn’t get in any flight tests in Quebec because the day all my equipment was ready was the day I had to send it all on the ship going to Anticosti. At this point I still didn’t know if the drone would fly.

with the payload.

and not drop this $15k piece of equipment that I didn’t own into the ocean.

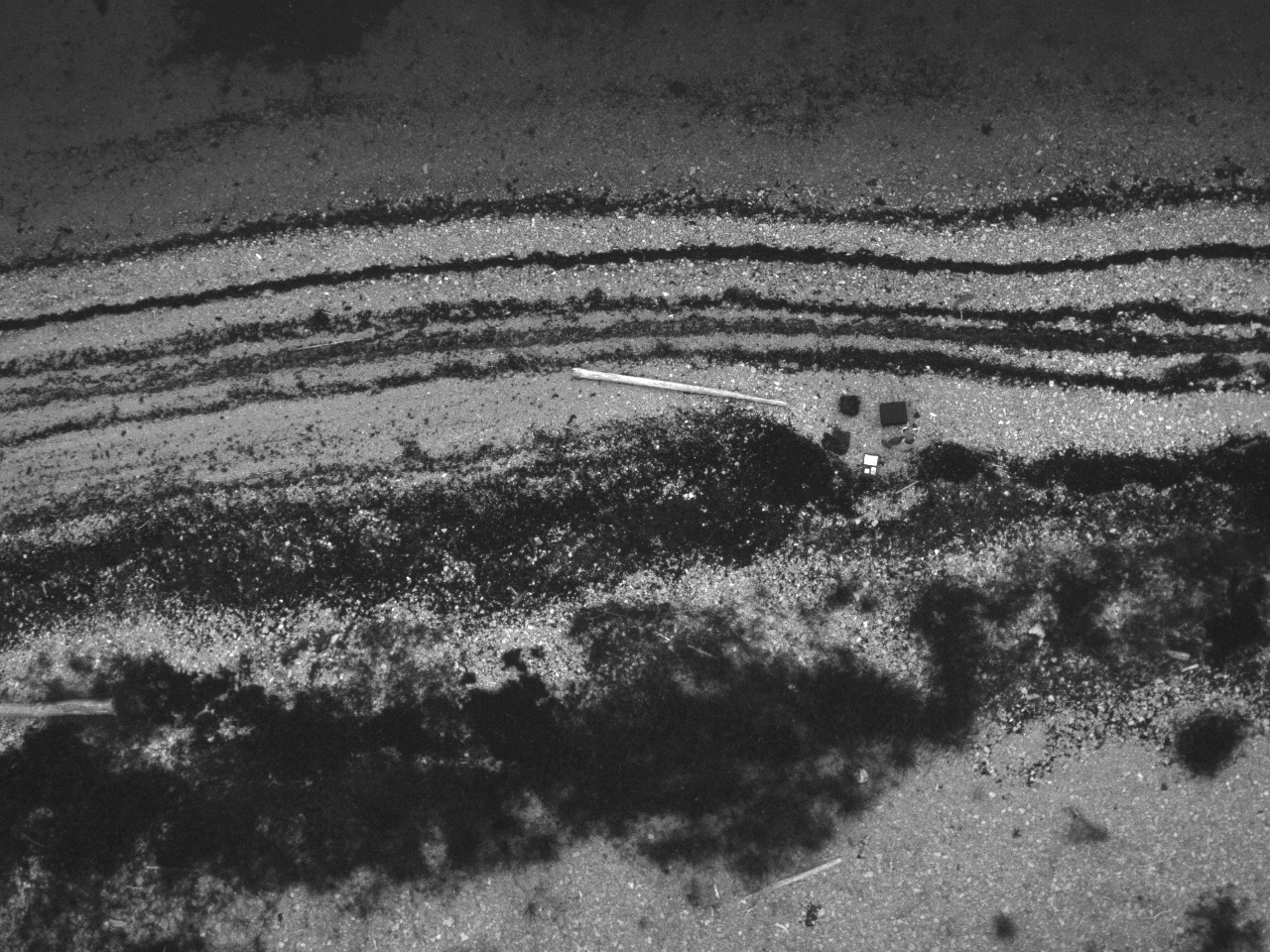

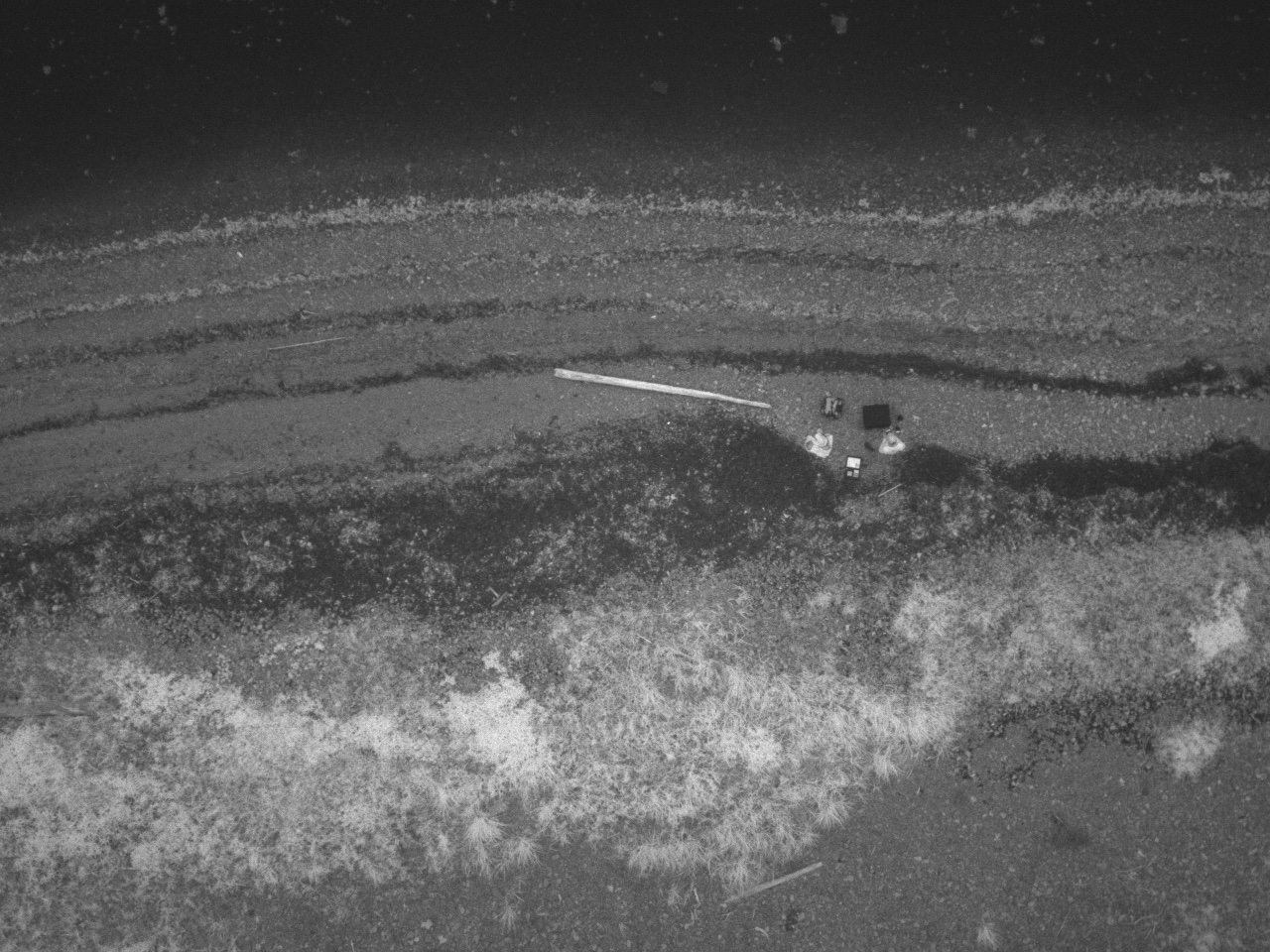

I reach the island and we’re greeted with 5 back to back days of terrible weather. No chance I’ll get to test the drone out now. Or would I?… Luck so had it that our team had set up our lab in a HOCKEY ARENA (bless Canada). Of course I should have factored that in! Lofted ceilings with plenty of open indoor space meant I could run my tests in a controlled windless arena with a 0% probability that I’ll drop this imager into the frigid abandon of Anticosti waters. Once I was confident with my tests, the next problem was finding a spot to fly. First problem was that within a 5.6 km radius of the Port Menier airport, there is restricted airspace. I don’t want no Feds coming down on my science. Also, the bathymetry (underwater landscape) of Anticosti Island didn’t help out in one bit because it was so so flat. As there was barely any slope, water depth that would be appropriate for our kelp may have been found almost a kilometer offshore - annoying for this drone pilot who would have to waste crucial flightime on these ragged batteries just to get to our sites of interest. Luckily I found a great compromise - Cap Gamache. A little inlet in the shelf where it breaks off to deeper waters a couple 100 m from the shore line. So for the three mornings of decent weather, I woke up early and embarked on a 12 km out and back hike through the woods and the shore to get to Gamache, where I’d fly till my batteries ran out of juice and then I’d go back and help out with other stuff the rest of the day. A lot of post-processing still needs to be done but one cool thing I saw is that just using the infrared sensor, I can see how fresh the washed-up algae is!

Diving on the island was wicked. Just algae and lobster - don’t need anything more in life do we? Because the underwater topography was so flat, you could see algae till the horizon (which in this case was maximum 10 m). Also because it was so flat, the presence of urchins (the scourge of algae) was vastly reduced. To explain this ecology a bit more, urchins can’t deal with waves you see and therefore like hanging out in deeper water. When the topograpy is steep, to get away from waves, urchins might have to move down a couple meters but when it’s flat like Anticosti, urchins would have to traverse kilometers before they’re out of the wave exposed area. Makes for a kelp paradise. Our dives were mainly to collect algae from 9 areas in a 30 m by 30 m grid. We’d bag ‘em, tag ‘em, identify ‘em, weigh ‘em, measure ‘em and note ‘em all down. I also dove with Raphaël Mabit who was another student using a fancy hypserspectral camera (camera but all wavelengths -ish) to identify the spectral signatures of kelp. These signatures could then be compared with satellite and the WISE imager to find out where exactly we can detect algae. Super interesting dives because with all the equipment you’re picking up and dropping down, keeping an eye on your buoyancy is key. Otherwise, you drop a weight and your inflated jacked is taking you where you don’t want to go - up.

The island in itself was really cool. We lived in an old lighthouse next to the wreck of the Galou, spent a good number of hours searching for fossils - this island holds some incredible evidence of the organisms from the Ordovician–Silurian period that perished in the 1st mass extinction (for reference, we’re causing the 6th). One day returning from the field, we came across a panicked lady with her baby in the car searching for her husband who had left on his bike and not come home. Remember, 150 people spread across the area of Jamaica. If you’re lost, you’re really lost. So we put together an adhoc search operation that involved me roaming through the woods on an ATV and jogging 5 km on the beach looking for bicicyle tracks. (he turned out to be fine - just smashed his bike into a tree and had to walk it back). One evening we even entertained Simon’s team from the research vessel the Coriolis, all disembarking with carrots and apples for the famous deer of Anticosti. Hilarious to see them swaying on land after a week and a half on sea. Funnily enough, the only Indian on the Coriolis found the only Indian on Anticosti and we chatted a while about life. Not speaking in Hindi for this long took a toll on our communication in the beginning but 5 minutes in and we were dropping shamelessly well-intentioned gaalis to smiling Quebecois faces ;)

All in all, quality trip. Achieved my objectives of testing out this drone tech and developing somewhat of an intuition of what extensive kelp flats look like. also warmed up the ecological centers of my brain for the craziness I’m about to see in Ungava Bay. Definitely an exercise to be dropped into a fresh new environment and piece together and ecological story in the matter of days. What a life.